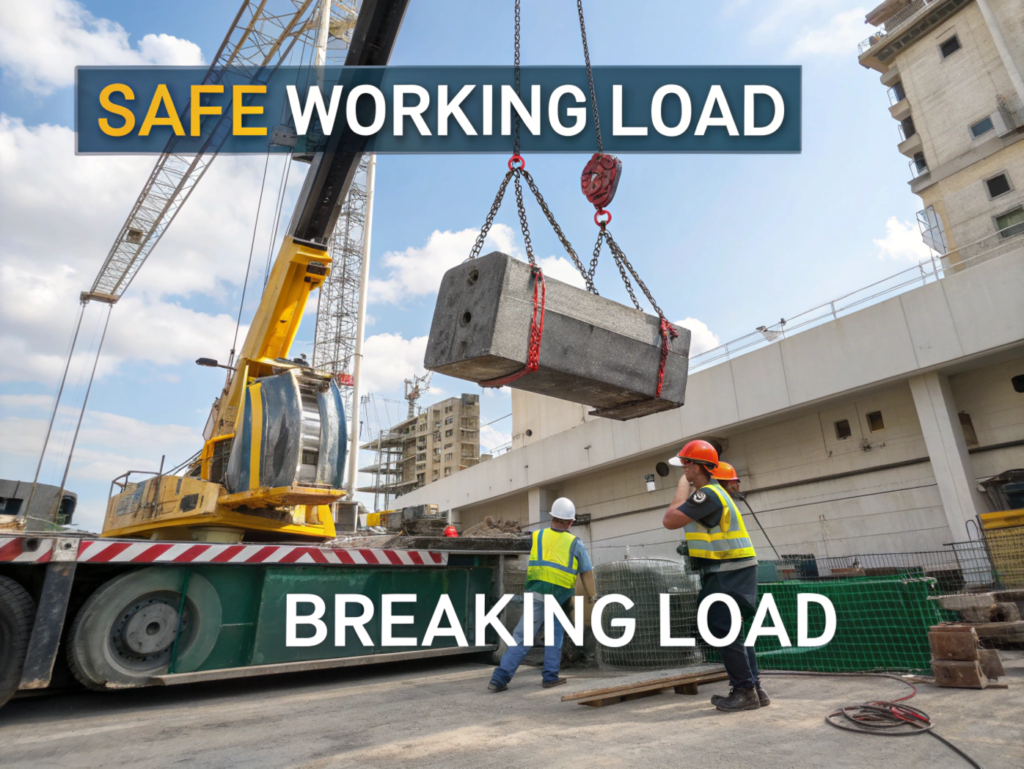

Lifting gear might look tough, but how much can it really handle before it fails—or before it’s unsafe to use?

Breaking Load is the absolute maximum a lifting product can take before failure. Safe Working Load (or WLL) is the safe limit you should operate under—usually 3 to 5 times less.

I learned this the hard way when we bought rigging gear based on breaking strength, not WLL. The gear passed load testing, but failed under repeated daily lifts. The lesson? Always check the working numbers, not just the max ones.

[Table of Contents]

- What is the difference between Safe Working Load and Breaking Load?

- How are SWL, WLL, and MBL calculated and related?

- Why is a safety factor used between MBL and SWL?

- Which value should procurement managers focus on when buying lifting gear?

- Is SWL still a valid term or has WLL replaced it?

What is the difference between Safe Working Load and Breaking Load?

These two values are often confused, but they are not interchangeable.

Breaking Load is the force that causes failure. Safe Working Load (WLL) is the max force allowed in real-world use.

DiveDeeper: One breaks, the other guides use

Breaking Load (also known as Minimum Breaking Load or MBL) is tested in controlled conditions—once. SWL or WLL, on the other hand, tells you how much you can safely lift every day. For example, if a G80 lifting chain from IVITAL has a breaking load of 24 tons, its WLL might only be 8 tons, applying a 3:1 safety factor.

How are SWL, WLL, and MBL calculated and related?

They’re tied together by safety factors—which vary by standards.

WLL (or SWL) = MBL ÷ Safety Factor. Most safety factors range from 3:1 to 6:1 depending on usage and regulations.

DiveDeeper: Use the formula

The ISO standard for lifting gear typically uses:

| Term | Meaning | Example Value |

|---|---|---|

| MBL | Minimum Breaking Load | 12,000 kg |

| WLL (SWL) | Working Load Limit | 4,000 kg (with 3:1 safety factor) |

| Safety Factor | Multiplier of safety margin | 3:1 (standard), 5:1 (critical applications) |

For IVITAL chains and slings, these values are clearly marked and tested according to international standards—no guesswork.

Why is a safety factor used between MBL and SWL?

It’s the insurance policy against unknowns.

A safety factor accounts for wear, misuse, dynamic loading, and real-world unpredictability. Without it, even perfect equipment can fail.

DiveDeeper: What’s not on the label

Dynamic loading, temperature extremes, or uneven load distribution can all reduce real-world strength. That’s why a 3:1 or higher safety margin is crucial. Engineers at IVITAL design with these risks in mind, especially in industries like construction and oil extraction where environmental variables are tough to predict.

Which value should procurement managers focus on when buying lifting gear?

Focus on the WLL, not just the Breaking Load.

Procurement decisions must prioritize WLL—it’s the real-world rating. Breaking Load is important but only relevant for calculating safety margins.

DiveDeeper: Buyer beware

I’ve seen catalogs advertise “Breaking Strength” in big bold font, with WLL buried in fine print. That’s misleading. Responsible suppliers like IVITAL always lead with WLL, because it reflects actual use cases. It’s what keeps your workers and your gear safe.

Is SWL still a valid term or has WLL replaced it?

In many industries, SWL is outdated. WLL is the standard term now.

Yes, WLL has largely replaced SWL in modern standards due to legal clarity and global consistency.

DiveDeeper: Terminology matters

SWL used to be common, but courts ruled the word “safe” could imply a guarantee. So ISO and other standards bodies now prefer WLL (Working Load Limit). IVITAL follows these standards across their lifting slings, chains, and cranes. If you’re reviewing a spec sheet, always look for WLL or Rated Capacity.

Summary

SWL and Breaking Load aren’t the same—WLL (formerly SWL) is for daily use, Breaking Load is the failure point. Know the difference, buy smart, stay safe.